The transition from one century to the next presents an opportunity to look ahead. This was indeed the case in 1900: gazing a century ahead would help leave a lasting impression, with this absolute future that the Year 2000 symbolized.

The future is a way to capitalize on dreams and imaginary visions, escape the pressures of the current day, and imagine a better world. While the agri-food industry was gradually becoming structured in the early 20th century, key economic players suggested that consumers collect images of the future.

These collections foreshadowed our current usages and presented scenes from future everyday life (mobility, health, communications, food, leisure, etc.). These old-fashioned goodies attest to an absolute belief in technological progress far beyond anything natural.

The future, and its promise of comfort and emancipation, became a pattern of consumption.

These plates, ordered and produced by the Vieillemard printing house for the 1900 Universal Exposition in Paris, were used by a variety of brands for their own advertising, after reworking them to add their brand name.

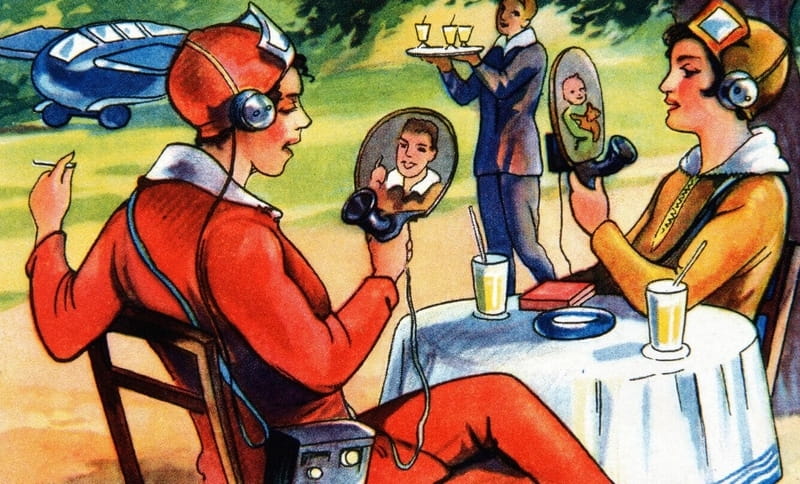

«Aviation in the year 2000». Whilst the Wright brothers made the first motorized flight 6 years earlier, this series of postcards are chromolithographic advertisements distributed to promote the ""Au Bon Marché"" department stores in Paris. I n them, we see the impact of airbone mobility on the services that the store would offer in the future."

"How our great-nephews will live in the year 2012!", a series of illustrations where a character's discourse highlights the plausibility of these predictions. Advertising postcards included in boxes of Lombart chocolates

"Fantasmes du futur" et "Techniques humoristiques", avec un esthétique joyeuse qui annonce les comics, la margarine Echte Wagner insère des petites vignettes dans ses produits où les visions sont de manière assumée délirante. Format 7 x 11 cm.

"Glimpses into the future". These collectors' cards for the Byrrh apéritif show us how technological progress would transform the main sectors of our economy. Series 24, Ateliers ABC, Paris, undated (circa 1930).

"The world of tomorrow". A series of 50 collectors' cards from 1938 included in cigarette packs from the Westminster Tobacco Company. It was possible to obtain an album from a tobacconist to store and display one's collection.

A series of advertisements placed in the press. Each of these ads presents a usage from the future, as envisioned by "men who are thinking about the world of tomorrow", in other words, by men who know how to savor a finely aged whisky.

"The year 2000" album. Aiglon Chocolate takes great care in its advertisement to present the theme of the future and looking ahead, which allows it to boldly claim the permanence of its brand. Album for 130 collectors' cards, Format: 8 x 11 cm

Life in the year 2000, Album #3 "We are now on the cusp of this future, with prospects both terrifying and grand, that will unfold before our amazed eyes. We're thinking ahead, in other words, we're a step ahead of the future, sketching out a stunning vision of human life in the year 2000. High Speed, Radar, Television, Propulsion into outer space, Atomic energy, Cosmic rays, Massive projects...such are the many Scientific elements, subjugated by mankind for its comfort, enjoyment, and, we hope, Universal Peace."

During the Second World War, and right after it, a different approach, blending innovation, the conquest of markets, and communications, emerged. It arose overall from heavy industry, energy companies, or networked enterprises.

These firms asked illustrators to portray future visions that attested to the fact that their industries best embodied, and constructed, how we would live in the future. Prophecy thus became utilitarian.

"Each worker has a part in Utah's future" Three characters representing civil society contemplate a dream city of the future from the picture windows of a building in the desert. New usages and habits in this city take shape before the eyes, as though every person had a role to play in its development. The postwar world belongs to these hard workers!

Radio, TV, and electrical research General Electric, one of the largest American conglomerates of that era, included energy business as well as the production of electronic products, and with this advertising campaign, it aimed to win the hearts of the public. This campaign didn't promote any specific product, but rather a new field: electronics, which would transform everyday life.

The American economy was mobilized for the war effort. It had been a few years since transport infrastructure had been a priority, and service was deteriorating. The American Railroad Association therefore made a bet on the American dream: it launched a series of illustrations to promote the incredible experience of the train of the future.

This transport industry supplier that produced axles foresaw vehicle super-specialization: they would be for single-task usage, and, clearly, would each need axles of their own!

This motor oil maker predicts a future where machines replace humans in terms of both labor and leisure. Technological progress makes these visions desirable, and nothing is said about the end of work nor about alienation.

"Behind man's conquest of the skies... a master's touch in oil" "Flying saucer - experimental military craft today - forerunner of your cloud car of tomorrow..." "Wherever there's progress in motion - in your car, your plane, your farm, your factory, your boat, your home - you, too, can look to the leader of lubrification"

While magical electricity became progressively more common in the interwar period in America, the post-war period pushed the promise of this energy source even further. Far more than just technological advances, what the union of independent power utilities promised was a real revolution in our usages and leisure time!

Interface - a portfolio of probabilities The American steel syndicate ordered a portfolio of illustrations from Syd Mead, the famous designer who would subsequently reign supreme in Science-Fiction films. Starting with a predictive calendar, he thus depicted around twenty scenes from everyday life in the future: individual transport and the automobile would predominate

In the 1970s the Princeton physicist Gerard O’Neill, with the help of NASA Ames Research Center and Stanford University, held a series of space colony summer studies which explored the possibilities of humans living in giant orbiting spaceships. Colonies housing about 10,000 people were designed and a number of artistic renderings of the concepts were made. Trois études d'été sur les colonies spatiales ont été menées à la NASA Ames dans les années 1970: les colonies toroïdales, les sphères bernales et les colonies cylindriques. Un certain nombre de rendus artistiques des concepts ont été réalisés. Scans de David Brandt-Erichsen. Illustrations: Don Davis, Rick Guidice

During this glorious era, when technical progress made social advancement possible through consumption, brands flocked to a new format, the exposition, and invited their potential clients to a sensory experience of the future.

This became a dream factory that brands could use through entertainment, as an attraction. These exhibitions brought new energy to universal expositions that had previously been simple demonstrations of technological inventions. Now, through elaborate settings, they foreshadowed the real promise of transformed usages.

The promotional film for the event in Technicolor eloquently recounts this epiphany on the future as reflected in these types of exhibitions: a rather old-fashioned couple arrives at the World's Fair in a horse-driven cart, they discover a multitude of technological marvels and new entertainment, and, that evening, they leave the fair in an automobile they've purchased on site: that says it all

In this film, the Middleton Family visits the 1939 New York World's Fair. As their name and Indiana origins suggest, the Middletons are designed to represent the middle class response to the Fair's imagined future of consumables and social improvement. The film is classic corporate spin. The Middletons visit the Fair, but they only tour the Westinghouse Building. They explore a Time Capsule, a television display, the Playground of Science, the Junior Science Hall, the Hall of Power, the Hall of Electrical Living, and the Battle of the Centuries. The latter is a humorous contest between "Mrs. Modern" and "Mrs. Drudge" in their efforts to wash dishes in front of a cheering audience. Mrs. Modern uses a gleaming Westinghouse dishwasher while Mrs. Drudge is dependent upon elbow grease alone. Predictably, Mrs. Modern is victorious as is the Westinghouse vision of an electrical future.

General Motors asked Norman Bel Geddes to create a gigantic installation over nearly 35,000 m2 entitled "Futurama: Highways and Horizons". Made in collaboration with Albert Kahn, it presented a scale model of a vision of the world 20 years in the future, a world built around the personal automobile. Over 70,000 visitors per day were invited to take a seat in a mobile lounge chair that moved at a speed of 2 km/h above the gigantic mock-up. 552 people were taken along this 16-minute voyage that hovered over the city of the future, with its 50,000 model buildings and 7-lane highways for automobiles driving at a variety of speeds. In many ways, this exhibit was a mix of design and the cinematic arts: this projecting of a certain view of the future, so that it may come to pass, had to be experienced physically and emotionally.

General Motors asked Norman Bel Geddes to create a gigantic installation over nearly 35,000 m2 entitled "Futurama: Highways and Horizons". Made in collaboration with Albert Kahn, it presented a scale model of a vision of the world 20 years in the future, a world built around the personal automobile. Over 70,000 visitors per day were invited to take a seat in a mobile lounge chair that moved at a speed of 2 km/h above the gigantic mock-up. 552 people were taken along this 16-minute voyage that hovered over the city of the future, with its 50,000 model buildings and 7-lane highways for automobiles driving at a variety of speeds. In many ways, this exhibit was a mix of design and the cinematic arts: this projecting of a certain view of the future, so that it may come to pass, had to be experienced physically and emotionally.

House of the Future designed in 1956 by Alison Smithson with her husband, Peter Smithson for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition. Unlike other works by the famous architect couple, the House of the Future is not an architectural project, but a scenographic mock-up at full scale of a living unit for a childless couple, set twenty-five years in the future. The house is spatially detached from the outside; wired acoustics are the only way it interacts with the outside world. The door elevation shows a speaker and microphone system above a mailbox, all to be installed to the left of the blob-shaped, electronically controlled entry door. The line between commodity and fiction is deliberately blurred: flanked by existing pieces such as the “Tellaloud’ loud-speaking phone” manufactured by Winston Electronics Ltd., various modern kitchen equipment and an Arteluce lamp from 1953, imagined devices such as after-shower body air-driers and telephone message recorders are exhibited in the house. Alison Smithson did everything, including designing the clothing that the models wore in the house.

House of the Future designed in 1956 by Alison Smithson with her husband, Peter Smithson for the Daily Mail Ideal Home Exhibition. Unlike other works by the famous architect couple, the House of the Future is not an architectural project, but a scenographic mock-up at full scale of a living unit for a childless couple, set twenty-five years in the future. The house is spatially detached from the outside; wired acoustics are the only way it interacts with the outside world. The door elevation shows a speaker and microphone system above a mailbox, all to be installed to the left of the blob-shaped, electronically controlled entry door. The line between commodity and fiction is deliberately blurred: flanked by existing pieces such as the “Tellaloud’ loud-speaking phone” manufactured by Winston Electronics Ltd., various modern kitchen equipment and an Arteluce lamp from 1953, imagined devices such as after-shower body air-driers and telephone message recorders are exhibited in the house. Alison Smithson did everything, including designing the clothing that the models wore in the house.

Monsanto House of the Future Modernistic house on display in Tomorrowland at Disneyland from June 12, 1957, until December 1967.

Built of plastics, the four-winged, cantilevered house featured the latest in furniture and appliances, along with intercoms and other gadgets that were uncommon in the homes of the time.

By 1967, the future had caught up with the house, so preparations were made to tear it down. But, it was so well built that when the wrecker’s ball struck the house, it merely bounced off. Eventually, the demolition experts had to take their saws and crowbars and pry the place apart piece by piece.

The promotional film that we show here demonstrates the effect intended by this attraction installed within a theme park: the woman visiting the home of the future starts to daydream and finds herself there...with her dishcloth of the future.

Whirlpool, amidst a thaw in the Cold War, produces an installation for the national American exposition in Moscow: here, it demonstrates The Miracle Kitchen. In this kitchen you can bake a cake in 3 minutes. And in this kitchen the dishes are scraped, washed and dried electronically. They even put themselves away. Even the floor is cleaned electronically. So welcome to this wonderful new world of cooking, cleaning, and homemaking. The computer was the center of the entire operation. A touch of the hand brings a refrigerated compartment to working level. Vegetable sink is located just below. The experimental kitchen has closed-circuit TV, air conditioning and a controlled system of colored lights.

In the 1950s, American public utilities launched a wide-ranging advertising campaign extolling the wonders of electricity? This campaign, entitled "Live Better Electrically", led to the creation of a "Medallion Homes" accreditation program, which highlighted home built around electricity and the quality of the electricity being supplied. Westinghouse wholeheardtedly embraced this concept with its "All-Electric House". Westinghouse offered promotional material for sixteen different all-electric home floor plans designed by five different architects, which sold for $10 each and spanned 900-2000 square feet. The architects were also contracted to design model homes in different regions of the country. The Westinghouse Total Electric Home officially opened for public tours on Sunday, April 24, 1960. In the film presented here, the company's spokeswoman, Betty Furness, takes viewers through this futuristic home, enthusiastically explaining how electricity would help residents live their lives to the fulllest.

Two American teenagers visit the Seattle World's Fair in 1962. They arrive by monorail before passing through the American Academy of Sciences. They linger there and try out all the newest communications technologies: push-button telephones, artificial dictation, beepers, call forwarding, remote-controlled ovens and air conditioning...such are the many promises that the teens of today now actually do live with.

“Man’s Achievement on a Shrinking Globe in an Expanding Universe", such is the theme of the 1964 World's Fair that returned to New York. IBM asked Eero Sarinen to design the building, a gigantic egg-shaped theater floating more than 30 meters over visitors' heads, and the Eameses to create the experience. For the Eameses, it was about sharing the coming influence of computers in modern society, and, to an even greater extent, revealing the similarity between the ways mankind and machines process and interpret information. After a spectacular walk up inside the egg, visitors took a seat in the theater that hosted a set-up of 22 multidimensional and multifaceted screens, where visitors could view a film by the Eameses entitled "Think". In it, they explored problem-solving techniques to resolve questions that were both common and complex, from the organization of a seating plan to town planning. Above the Ovoid theater, the Eameses created a exhibit, "Mathematica", a world of numbers that reveal how computers work. And lastly, they placed IBM products in a setting where demonstrations and activities showed visitors that computers would become an integral part of all our lives.

Radio and parts manufacturer Philco-Ford offered a fantastical, but serious look at the future. In the "1999 House of Tomorrow", the activities of each family member are made possible by a mainframe computer and center around products that are remarkably similar to those made by the sponsor. The energy comes from an autonomous fuel cell, which allows to control the environment, from an automatic cooking system and from a computer-assisted "education room".

Starting in the 1970s, the World’s Fair paradigm began to shift, and, in a clear move toward a postmodern spirit, brands were no longer able to sell a glorious future through technological advancements.

The move was from the promise of a rather distant future to the products just on the horizon; it was therefore no longer a question of selling the world of tomorrow, in itself, but of speaking to each individual in their everyday lives. Brands focused their tales of the future on small details and specific habits made easier due to concrete objects and solutions.

From that point on, one specific type of story became common: the usage scenario. Not able to predict nor commit to an overall picture of the future, so great were the cognitive dissonances, brands drew their focus back into everyday benefits: a business woman can get home earlier because she uses a flying taxi; a man sitting at his desk is hard at work, using technological tools, etc.

The rare scenarios depicting wholesale transformations in our everyday lives did exist, but were reflected in animated formats, as though this more distant, dreamlike medium were less binding.

Here is what, in Lacoste's view, the tennis player of 2083 could look like: tall, muscular, bionic, and dressed in a black-and-white jumpsuit.

His tennis racket features magnetic strings that allows for improved control, and his intelligent shoes recognize and adapt to the playing surface. He wears knee and elbow pads, because the power of his right stroke may lead him to fall, like a football player, leading him into a roll, like a judoka. To protect himself from the speed of the ball and from the sun, he wears a mask, which also gives his information about ball trajectory. He also wears a hard breastplate, which has replaced the iconic polo shirt. Its collar, short, trimmed sleeves, and the brand logo have, for their part, not changed!

To celebrate its 75th birthday, the brand chose to look into the future, with a creative concept championed by the Megalos agency (part of the CRM Company group) to support this anniversary.

In the "A Day Made of Glass" video, Corning depicts a world where real-time information is delivered seamlessly, and everyday surfaces are transformed into sophisticated electronic devices. It’s a world of mobile communication and connection… and it’s a world made of glass.

The Future Food District (FFD), a 7,000 sq. m. thematic pavilion that explores how digital technology can change the way that people interact with food, will be unveiled at tomorrow’s opening of Expo Milano 2015, “Feeding the Planet, Energy for Life.” Created by Italian design firm Carlo Ratti Associati, together with supermarket chain COOP Italia, the pavilion – lying at the heart of the exhibition grounds – explores how data could change the way that we interact with the food we eat, informing us about its origins and characteristics and promoting more informed consumption habits.

This film presents the potential ecosystem for the e-Palette concept car by Toyota. An autonomous electric vehicle, it is also a service platform that ensures the comfort of the city's inhabitants, whatever the season or usage of the vehicle: for retail, entertainment, health, work, learning, wellness, hospitality, food service, or just public transport.

These images show the economic potential and the quality of the experience provided by this vehicle, in the city of tomorrow.

How we will cook, eat, and socialize at home. Ideo helped IKEA envision how people's behaviors will shape the design of the future kitchen.

- The Modern Pantry encourages us to have a closer relationship with what we eat by storing food in transparent individual containers on open shelves rather than hiding it at the back of the fridge. The design makes it easy to be inspired by what’s on hand rather than going out to buy more, and it also saves energy: Induction-cooling technology embedded into the shelves responds to RFID stickers on the food’s packaging in order to keep the containers at just the right temperature.

- The Table for Living is designed to inspire people to be more creative with food and throw away less. At a loss for what to do with that leftover broccoli? Just place it on the table and a camera recognizes it and projects recipes, cooking instructions, and a timer directly onto the table's surface. Set the timer for how long you want to spend preparing the meal, and the table suggests recipes that can be completed in the window you have available. The table is a nifty solution for a smaller urban dwelling because it’s multimodal: Hidden induction coils instantly cool the surface when not in use, so it’s adjustable for working, cooking, or eating.

- The Modern Sink pushes us to be more conscious of our water consumption with a pivoting basin. It must be tipped to one side to drain toxic, or “black,” water, and to the other for safe “gray” water, which is not drinkable but can be filtered and used in a dishwasher or as nourishment for the cooking herbs that grow above the sink.

- The Thoughtful Disposal system is a response to the overuse of landfills, and reminds us of exactly what we’re throwing away. Users manually sort recycling from rubbish, and recyclables are then crushed, vacuum-packed, and labeled for pick-up, earning credits for the conscientious (and debits for the wasteful).

IKEA’s kitchen and dining range manager, Gerry Dufresne, explained that the Concept Kitchen 2025 is not really a functional kitchen, but rather “a tangible communication of what the behaviors of the future will be.”

This film presents a domestic environment of the future in a mega-city.

The Ikea catalogue from the Near Future Laboratory is an object of design fiction. It does not pretend to dictate the future or specifically forecast trends. Its mission is to foster dialogue around our everyday lives in the near future. The Ikea catalogue is a symbol of the popular culture of our era; apparently, it has been printed more times than Harry Potter books or the BIble. By fictionalizing the content of this object, it becomes a tool for exploring imaginary visions and critiques.

This conceptual film offers a look ahead from architecture firm Foster + Partners, on behalf of Nissan. Designed in extensive detail, this usage scenario unfurls throughout an entire city. Here, sidewalks, the entrance hall of buildings, the energy management of housing units, and more, are reinvented.

The need for a sustainable and innovative refuelling network is becoming vital as the market shifts toward alternative sources like electric power. Seamlessly integrating emerging clean technologies into the built environment is vital in creating smarter, more sustainable cities. The Fuel Station of the Future is a vision of the future of mobility and its role in the development of sustainable urbanism. The project reimagines how cars could be integrated into the urban landscape and be part of a holistic, sustainable solution that brings together transportation and energy production and distribution.

At the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) 2017 in Las Vegas, Hyundai Motor has revealed its ‘Mobility Vision’ concept that, in the future, will connect autonomous cars to living and working environments. Signaling the start of a new era, Hyundai Motor’s Smart House technology blurs the line between mobility and living and working space, integrating the car into the daily lives of users. The Smart House concept shown at CES is an important demonstration of Hyundai Motor’s plans for ‘Mobility Vision’, which places Connected Car technologies at the center of the home. The CES display suggests how the car could shed the image of a conventional vehicle, integrating itself with the living space when docked, before becoming a mobile living space when customers need to move around.

A playful research project that challenges the traditional idea of the car and explores how we can re-purpose it to create a more fulfilling life on wheels. Fully autonomous vehicles won’t simply be a form of transport. “Because we won’t have to worry about driving, vehicle interiors can expand to a point where we stop thinking of them as vehicles.” In the future of mobility, the car will no longer be just a way to get people and goods from A to B. Ultimately, Spaces on Wheels invites more people to envision the profound paradigm shift the development of self-driving cars could have on our everyday lives.

Urban Village Project is a new visionary model for developing sustainable, affordable and livable homes for the many people living in cities around the world. The concept, developed by SPACE10 and Effekt architects, looks at the way of designing, building, and sharing our future homes, neighborhoods and cities, so that they won't pollute more, can remain affordable, and can avoid widening social gaps. This urban village provides for:

- A modular construction system in wood, designed to be disassembled, and that can be prefabricated, flat-packed, and rapidly assembled on-site. This guarantees a more sustainable method of construction, which also emits less CO2, and offers a circular approach to the management and life-cycle of structures.

- A new economic model that considerably lowers the barrier of entry into the housing market, making high-quality housing affordable for users of all income levels, while establishing a connection between the developer and the consumer.

- Shared intergenerational living communities at the heart of our cities, with adaptable, high-quality housing connected to a variety of shared services and facilities, and a digital interface to meet everyday needs.

Woven City is a fully connected ecosystem powered by hydrogen fuel cells to be built at the base of Mt. Fuji in Japan.

This “living laboratory” will include full-time residents and researchers who will test and develop technologies such as autonomy, robotics, personal mobility and smart homes, in a real-world environment. We welcome all those inspired to improve the way we live in the future, to take advantage of this unique research ecosystem and join us in our quest to create an ever-better way of life and mobility for all.